By Curt Cavin Published March 19, 2021 - https://www.indycar.com/News/2021/03/03-19-Millican

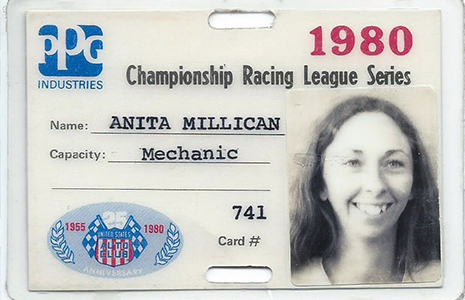

Look at Anita Millican’s smile on her 1980 CART credential. There is joy, yes, but it overrides the pain of a difficult journey in an awkward era of the sport.

This credential not only was the first permitted to Millican after nearly a decade as accomplished INDYCAR mechanic and fabricator, it was the first such allowance to a female mechanic in a sport with roots traced to the early 1900s.

Women are still making inroads in auto racing, but this was among the most difficult first steps, and it exhausted Millican, who retired in 2012 as an elite machinist and shock absorber specialist. She endured ridicule and chauvinism at nearly every turn, and it took years before payment for her work wasn’t included in checks to her husband.

Women are still making inroads in auto racing, but this was among the most difficult first steps, and it exhausted Millican, who retired in 2012 as an elite machinist and shock absorber specialist. She endured ridicule and chauvinism at nearly every turn, and it took years before payment for her work wasn’t included in checks to her husband.

Keep in mind that before 1971, women weren’t allowed in an INDYCAR garage. Think about that. Couldn’t pick up car keys or deliver a sandwich. Couldn’t be with a husband in the hours leading up to a dangerous race. It took a lawsuit from a journalist to open even the first door, and it was still another nine years until female mechanics were credentialed. Before that, women like Millican sold parts out of a trailer outside the fence even as she supported the operation back at the shop. All the while, a bandana hid her long hair.

Blending in, it’s called.

“Head down, elbows out, mouth shut,” Millican said.

But breaking through in a man’s sport was exhausting, and it should be celebrated beyond Women’s History Month.

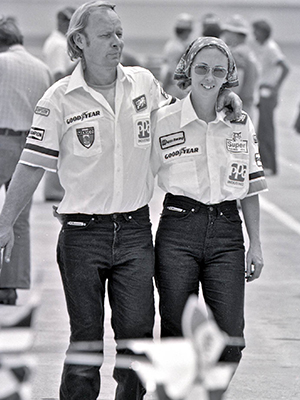

Millican was a pioneer in so many ways, including being the first woman to go over the pit wall during the Indianapolis 500. For two seasons she served as the vent “man” for Machinists Union pit stops – and remember, speeds weren’t restricted and helmets not required. Yet as brave as she was, she often had to have a fellow crew member walk with her to pit road to gain access, catcalls hurled her way.

“In those days, women in racing were there, shall we say, to be (pretty) – dressed perfectly, fingernails nicely painted and flirting, anything to get a team shirt,” she said. “I worked with men and men only, and I absolutely had to have them trust me, so there was no flirting. I just did my job, and that helped with some of the chauvinism.

“I had to be very, very careful and conscious, even in uniform. I got called many bad words by a lot of people.”

One day, Millican was working in the shop she and her husband, Howard, an established INDYCAR mechanic and fabricator, built on 5 acres west of Indianapolis Motor Speedway. A visitor entered the room, dumbfounded to see her with tools in hand.

“What are you doing?!” he said with a raised voice. “I’m going to tell Howard!”

Howard happened to have followed the man into the shop, and he was amused. Anita was not, mostly because it was an outburst she had experienced even as the couple built a reputation for craftsmanship.

The Millicans created one of the earliest wind tunnels by cutting a car in half and mounting it on the wall. Placing engines at one end of the shop and opening the doors on the other, they ran tests in all sorts of weather, including snow. Their work changed the leading edge of wings forever.

In that Danville, Indiana, shop, Anita created computer programs allowing data to be analyzed as Howard ran the engines. Together, they invented what’s believed to be the first shock dynamometer and developed revolutionary data acquisition principles, largely behind the scenes because that was the accepted way of the day.

Millican remembers a moment working in a shop on Gasoline Alley south of IMS. A young man entered, putting his hands on his hips, disgusted that she was “taking a man’s job.” She once had a reporter ask how much she weighed.

“Can you imagine a male mechanic being asked that?” she said.

The lack of respect grew wearisome.

“When I retired, I was physically, emotionally and mentally burned out to the point I almost couldn’t lift my arms from all the years of trying and struggling, and the prejudice,” she said, now 74.

Millican appreciated her opportunities in the sport and loved nothing more than working alongside Howard to make fast race cars, but she feels “sad” that she and other women years ago weren’t given credit for their contributions and were often treated poorly. However, she appreciates the progress the sport has made in the past 50 years, especially recently.

Today, women are not only INDYCAR drivers – there have been nine in the “500” -- but women are engineers, mechanics and executives. Cara Adams is Firestone’s chief engineer, leading the group arguably most essential to the safety of INDYCAR drivers. Firestone’s top INDYCAR decision-makers are women, too, and Beth Paretta will be the car owner of Simona De Silvestro’s car in this year’s “500.” The goal is to have women on the Paretta Autosport crew.

Bandanas are no longer necessary.

Millican credits her husband for not only opening racing’s door to her, “but holding it wide open” for her. Howard lost a five-year battle with cancer in 1995.

Millican credits her husband for not only opening racing’s door to her, “but holding it wide open” for her. Howard lost a five-year battle with cancer in 1995.

“Without him, I couldn’t have even stuck my little finger in the door,” she said.

Millican went on to become one of the top shock experts in the sport. After Howard died, she joined Roger Penske’s prestigious shock company in Reading, Pennsylvania, working there six years, a key cog in Helio Castroneves and Gil de Ferran winning Indy three consecutive years.

While Millican has painful memories, she has “millions” of fond ones, many featuring Bobby Unser, who went to high school with her husband. The three worked together for years, including in 1980 when Unser managed an Albuquerque-based team.

Millican remembers Unser gathering the crew for a series of pre-May instructions. Emphatically, he said there would be no women allowed in the garage. Anita piped up. “What would you like me to do during the month?”

She enjoyed his reaction: “Bobby had that great Bobby Unser laugh and he said, ‘I didn’t mean you, son.’”

Millican became so respected that she became one of the first card-carrying female members of the Machinists Union. The union often sought to publicize her involvement as a racing pioneer, but she usually declined, assuming it would detract from the cohesiveness of the team.

“There are no stars on a team, only a team,” she said in citing one of her favorite Penske quotes.

Not surprisingly, the humble Millican doesn’t talk much about her contributions to teams such as Galles Racing, which won the 1992 “500” with Al Unser Jr. But the Unsers are among the many who revere her and Howard.

Millican now lives on a Costa Rica orchid farm with her four dogs. She misses Howard, whom she had a bond so strong they held hands at every opportunity, including in restaurants. They had prepared this Central America retreat adorned by the flowers designed to be their retirement home, but he never got to see it in full bloom.

“We were always together and married 30 years, and people would ask when the ‘honeymoon’ would be over,” she said. “Howard would say, ‘When the honeymoon is over, so is the marriage.’”

They were a team, working side by side in the sport they loved, breaking barriers as they went.

“We had the most wonderful, incredible, exciting life traveling the world racing,” she said. “I used to say I was always exhausted but never bored.”